Here’s what we’re thinking about

Why Your PR & IR Teams Need to Be Besties (Especially Right Now)

When PR and IR teams aren't aligned, your brand is at risk. Discover why close collaboration between public relations and investor relations is more essential than ever and how to build a stronger, more unified approach.

Global Trade System Has Long Been in Transition

An in-depth look at the evolution of the global trade system since World War II and how Trump’s tariffs mark the latest shift in a long history of imbalance and transition.

Mid-Year Marketing Check-In: A 5-Point Strategy Checklist for Financial Brands

Get your financial marketing strategy back on track with this 5-point mid-year checklist.

PR Is the New SEO. And Vice Versa.

As AI reshapes search, PR and SEO must evolve together. Learn how forward-thinking brands are integrating media, messaging, and search strategy to build trust with both humans and algorithms.

From Legacy to Longevity: How Branding, Tech, and Transparency Future-Proof Family Offices

As the Great Wealth Transfer reshapes family offices, branding, technology, and transparency are becoming essential to future-proofing legacy wealth.

The ‘LinkedIn Run Club’: Industry Execs Adopt Influencer Tactics to Humanize Firms

Vested Managing Director Eric Hazard shared his thoughts with FundFire on the rise of execs-turned-finfluencers and how platforms like LinkedIn are reshaping leadership visibility.

DigiFi Discourse: The GENIUS Act, Bitcoin Highs, and Memecoins Driving Wider Adoption

Tune into DigiFi Discourse, the video series with Vested Senior Account Executive Gabby DiCarlo and AssetTV.

How PR and IR Interact: The Stakes Have Never Been Higher

Current economic uncertainty makes a strong comms-IR relationship more crucial than ever.

Return of the Commonwealth?

The UK-India trade deal signals a shift in global trade dynamics, recalling Commonwealth-era openness while offering long-term opportunities, and unavoidable tradeoffs, for both nations.

Is AI Empowering PR or Just Making It Louder?

AI is reshaping the PR industry in powerful ways, but the key lies in using it thoughtfully to enhance, not replace, human insight in communications.

The Power of Identity in Storytelling - Reflections as an AANHPI Marcomms Professional

Reflections from the Vested team on how identity shapes storytelling, the power of representation, and the importance of authenticity in marketing and communications.

Banks Are Winning Big on Affiliate Marketing. Are You Missing Out?

How affiliate marketing is reshaping bank customer acquisition.

Running the Numbers on Your Summer Kick-Off

Where consumers can expect higher prices or some sweet sales this Memorial Day Weekend.

Stablecoins Took Toronto by Storm: Takeaways from Consensus 2025

Crypto took center stage in Toronto as CoinDesk’s Consensus 2025 spotlighted stablecoins, regulation, and infrastructure. With big names and bold predictions, the event signaled a new era for digital assets.

Bank Branding: Ideas, Inspiration & Best Practices

Discover the impact of branding for financial services companies, particularly banking institutions.

What We Heard at Financial Narrative’s 2025 Spring Summit

Insights from Financial Narrative’s 2025 Spring Summit, where top finance marketing and communications leaders explored trust, AI, global branding, and the future of storytelling in a rapidly evolving industry.

NYC Fintech Week 2025: Key Takeaways from Vested

Explore key takeaways from NYC Fintech Week 2025, including insights on bank-fintech partnerships, event strategy, inclusive leadership, and the future of fintech innovation.

Buffett's Farewell: Reflecting on His Simple Words and Succession Surprise at Berkshire

Warren Buffett’s retirement at 95 marks the end of an era at Berkshire Hathaway.

Sorry Prospects for the Once-Unbeatable German Economy

Germany’s economy is struggling under the weight of high energy costs, declining industrial output, shifting global trade dynamics, and looming tariffs, posing serious challenges for the country and the broader EU.

Bank Marketing Leaders Reallocate Dollars in Urgent Search for Performance

Facing tighter budgets and performance expectations, banks are reevaluating how they’re allocating advertising dollars in 2025.

Building a More Financially Literate Future for All

Financial literacy in the US is declining, but progress is possible.

Harnessing the Power of Finfluencer Marketing

5 ways fintech and financial services marketers should approach influencer marketing.

In a Changing Media Landscape, Authenticity and Connection Matter More than Ever

AI is not only thing disrupting financial services advertising.

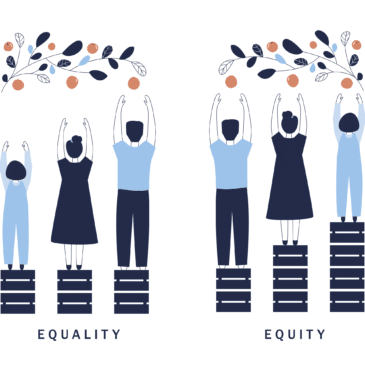

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Aren’t Optional. They’re Essential.

While some organizations may be pulling back on DEI, here at Vested, we remain as committed as ever.

When Your Brand Checks into The White Lotus

Duke University’s unexpected portrayal in The White Lotus Season 3 highlights the challenges of brand safety in popular media.

CEOs Remain Silent as Trump Tariffs Shake the Market

As Trump’s new tariffs create market volatility, many CEOs remain silent, opting for strategic caution over public commentary.

Has the Stock Market Slide Signaled Recession?

Analyzing recent stock market declines and economic indicators, Ezrati explores the likelihood of a recession, historical patterns, and the potential impact of policy decisions.

Celebrating Women in Finance: An Inspiring Evening of Connection and Conversation

We hosted an inspiring evening of connection and conversation for leading women in finance.

Trump's Tariffs, Musk's AI Ambitions, and a Fintech Wake-Up Call

The news you need to start your week.

Why Financial Brands Must Think Like Publishers in the Age of AI

Financial brands must embrace a publisher mindset in the AI era. AI-driven content strategies build deeper connections, enhance storytelling, and optimize engagement in real time.

Digital Marketing for Financial Services: Tips, Ideas & Strategies

Unlock the power of digital marketing in finance with Vested. Drive engagement and build trust with expert strategies tailored for financial services.

Social Media for Financial Services: Benefits, Tips & Strategies

Discover powerful strategies for financial services social media marketing with Vested. Maximize engagement and grow your brand effectively.

Master Selfie Videos for LinkedIn Growth

Master the art of selfie videos for LinkedIn. Learn why authentic, unfiltered content drives engagement, what video formats work best, and how to create viral-worthy videos with just your phone.

March Madness Ad Surge: News to Start Your Week

The news you need to start your week.

The Tide Is Turning: What to Know about the Trump Administration’s Digital Assets Priorities

The Trump Administration is pushing forward on digital assets, with new regulations, a strategic Bitcoin reserve, and a focus on tokenization.

Trump Backs Stablecoins Amid Market Turmoil and Corporate Shifts: News to Start Your Week

The news you need to start your week.

The Regulatory Horizon for Finance

The Trump administration is reshaping financial regulation, from shutting down the CFPB to easing merger restrictions and navigating Supreme Court rulings

Our Branding Philosophy: How to Tell an Impactful Story

From understanding your target market to defining your brand personality, we break down the key steps to building a powerful brand.

Economic Uncertainty, Debt Crisis Warnings and Oscar Night 2025: News to Start Your Week

The news you need to start your week.

Leverage Customer Analytics and Insights in Financial Services Marketing

Learn how financial brands can use customer insights to enhance marketing strategies, improve engagement, and drive ROI.

Tackling the Challenges of Content Marketing in a Regulated Industry

Discover the strategies to balance creativity and compliance effectively.

German Election Shake-Up and U.S. Inflation Fears: News to Start Your Week

The news you need to start your week.

The Complete Guide to Public Relations for Financial Services

Managing Director Eric Hazard shares the complete guide to public relations for financial services.

Content Marketing for Financial Services: Tips, Ideas & Strategies

Unlock the power of content marketing in finance with Vested. Drive engagement and build trust with expert strategies tailored for financial services.

A Different Game Day for CEOs: Super Bowl Ads Aim to Drive Shareholder Interest

Pfizer and Meta used Super Bowl ads to shape corporate strategy, market perception, and investor confidence.

Romance & Receipts: Valentine's Day Spending 2025

Valentine’s Day spending is set to hit a record $27.5 billion, with more consumers celebrating and splurging on gifts, dining, and experiences.

2025: The Year of Non-Traditional Media

As traditional media declines and trust erodes, non-traditional platforms like podcasts, YouTube, and Substack are shaping the financial PR and advertising landscape in 2025.

Observer 2025 PR Power List: Vested at #3

Vested comes in at #3 on the Observer PR Power List 2025.

Everything We Know About Trump's Tariffs: News to Start Your Week

The news you need to start your week.

Protectionism, Tariffs and Investment Flows

Protectionism is on the rise in Washington, with escalating tariffs and blocked foreign investments shaping U.S. trade policy.

Vested Perspective: World Economic Forum 2025

Explore key insights from the 2025 World Economic Forum in Davos, from AI's transformative role in financial services to themes of sustainability, trust, and innovation shaping our collective future.

Striking the Right Balance Between CEO Visibility and Security

Discover strategies to balance CEO visibility and security, ensuring effective leadership while minimizing risks in today’s complex environment.

PPC for Financial Services: A 2025 Playbook

Create impactful PPC strategies with actionable tips on audience targeting, ad copy, and compliance management.

Five Questions For Post-Merger Communications

The five essential questions for effective post-merger communication, focusing on integration, alignment, and fostering a unified culture.

How to Do SEO for Financial Services: Ultimate Guide for 2025

Drive qualified traffic to your financial website with our comprehensive SEO guide. From E-E-A-T to YMYL, we cover essential techniques.

How to Successfully Build an Investor Relations Strategy

Learn the key steps to create a successful investor relations strategy, engage with investors, and enhance corporate communication.

Elections Across the World Carry Distinct Economic Messages

Diving into the economic ripple effects of 2024's global elections, as voters prioritize living costs, growth, and national interests.

Effective Strategies for Launching Financial Products

Launching financial products successfully requires the right strategies. Explore actionable tips, real-world examples, and expert insights into effective financial product marketing.

Advertising Trends Shaping 2025

Diving into the key advertising trends shaping 2025, from AI-driven targeting and Big Tech platforms to emerging creative tech and media strategies.

Financial Outlook 2025: Trends and Topics for the Year Ahead

Take a closer look at the trends Vested is monitoring across financial services as we move into the new year.

The Fed’s High Wire Act

Explore the Federal Reserve's delicate balancing act between inflation control and economic growth, as recent rate cuts raise questions about policy direction and market expectations for 2025.

Making the Most of Influencer Marketing for Financial Services: A Guide

Influencer marketing brings engaged audiences when done well. Use this guide to build your strategy for marketing your financial services.

The Power of Great Content: Unlocking Brand Awareness, Loyalty and Growth

Discover how high-quality messaging, thought leadership, and digital campaigns can build trust, boost visibility, and drive meaningful engagement for long-term success.

International Financial Comms and Marketing Agency Network Launches

A new international network of independent marketing and communications consultancies, specialising in financial services, has launched.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative: A Costly and Troubled Scheme that Beijing Will Support Nonetheless

Explore China's ambitious Belt and Road Initiative, examining the economic burdens it places on Beijing and the strategic influence it secures in Africa.

How to Maximize ROI in Financial Services Marketing

Looking to stretch your marketing budget? Discover top strategies to increase ROI and get the most out of every dollar spent.

Preparing Financial Firms for Election Uncertainty

Prepare for election uncertainty with clear communication strategies. Learn how to align internal teams, proactively engage clients, and navigate market volatility through transparent, expert messaging.

Make the Most of Your Year-End Marketing Budget

As the year draws to a close, now is the time for marketing teams to strategically invest their remaining budget in enhancing brand presence, engaging social media initiatives, internal training, and research-driven decisions to set the stage for success in 2025.

Gramercy Financial Marketers' Forum: AI and the Future of Financial Marketing

Read the summary from David Simpson's panel discussion on 'AI and the Future of Financial Marketing'.

Unlocking C-Suite Communication: Building Business Acumen and Influence

The top learnings from Ragan’s Internal Communications Conference at Microsoft’s Headquarters in Redmond, WA.

Podcasts Could Become the New Secret Weapon in Boardroom Battles

Elliott Investment Management is using an unconventional podcast series to influence Southwest Airlines’ boardroom battle, directly engaging investors and reshaping corporate communication strategies in the process.

Affiliate Marketing Guide for Financial Services

Learn how affiliate marketing can drive growth in financial services. Explore strategies for promoting financial products through targeted partnerships.

Effective Marketing: Making Financial Services Valuable to Millennials and Gen Z

Millennials and Gen Z grew up in unusual and rapidly changing financial times. Learn how to market financial services to the younger, but increasingly influential, generations.

From Trump, Biden or Harris, Sovereign Wealth Funds Can Be Dangerous

Sovereign wealth funds proposed by Trump and Biden could reshape the U.S. economy, but carry risks like stifling innovation and undermining government accountability.

The Rollercoaster Journey of Reddit and Financial Services

Explore the rise of Reddit in financial services, from its impact on search results to the challenges and opportunities it presents for brands.

Partnerships in Progress: Celebrating Collaboration

Celebrating the power of collaboration, Vested UK reflects on 2024's successes and looks ahead to a strong finish.

How Often Should You Email? (It's More Than You Think)

Learn how to optimize your email marketing strategy by sending more frequent, personalized emails, with tips on delivering fresh, high-quality content.

I’m an Economist: 3 Reasons I Believe Harris’ Opportunity Economy Could Help Retirees

Discover how Kamala Harris' "opportunity economy" could impact retirees.

Return to Office Conversation Continues: News to Start Your Week

The news you need to start your week.

Hop Off the New Lead Treadmill

Discover how shifting your focus from constantly acquiring new leads to nurturing long-term customer relationships can stabilize revenue and increase business growth.

The Influencer Effect: Benefits, Strategies and Considerations for Influencer Marketing

Explore "The Influencer Effect" and discover how influencer marketing can elevate your financial services brand.

The Harris-Walz Campaign Reveals Its Tax Plans

Explore the Harris-Walz campaign's tax proposals, which build on Biden-era plans with significant changes for corporations and high-income individuals.

Santa, The Easter Bunny, and the “Soft Landing”

Delve into the historical trade-offs between inflation control and economic downturns, plus the complexities of current monetary policy amid evolving pressures.

Trump Wants A Say In Framing Monetary Policy

Former President Trump’s call to overhaul the Federal Reserve's independence echoes historical patterns of presidential influence.

What China Policy Will Emerge After The Election?

Kamala Harris and Donald Trump, despite their differing policy visions, are likely to maintain or intensify an adversarial stance towards China, with shared hostility toward Beijing’s trade practices.

What Communicators and HR Can Learn from the Recent Jobs Report

Being a consistent, empathetic advisor is a big help.

Sustainable Snapshot: 2024 Paris Olympics

Tune into Sustainable Snapshot, the video series with Vested Director Marian Daniells and AssetTV.

How Disruptive is AI Economically?

Explore the economic impact of AI and understand how past patterns of technological change inform our expectations for AI's effects on the workforce and economic disparities.

Facts and Figures of the 2024 Summer Olympics

A look at the numbers surrounding the Paris Summer Olympics.

Is YouTube the New CNBC? TV Trends to Consider for 2025

Are you adapting your advertising strategy to the changing media consumption landscape?

The Complete Guide to Brand Strategy for Financial Services

Discover essential strategies for crafting a powerful brand in the financial services sector.

At the Vested Library with James McKenna at Finastra

James McKenna, senior PR leader at Finastra, shares his thoughts on speaking to various audiences, keeping the customer at the center, and his top tips for working with an agency.

How Biden Stepping Down as the Democratic Nominee Could Impact Your Wallet

As election news continues, learn about potential changes in taxes and inflation that could affect your financial future based on the next presidential candidate.

I’m an Economist: Here Is What I Would Predict for Inflation If Kamala Harris Were To Replace Biden

Explore the potential economic impact of a Kamala Harris presidency on inflation.

Internal and External Communications Considerations During Special Situations

Explore how organizations can effectively manage internal and external comms during critical events, ensuring empathy, clarity, and brand protection.

Comms Lessons From the Paramount-Skydance Merger

A closer look at the impacts that the M&A process can have on employees and culture.

Building a Fintech Marketing Strategy with 2024 Trends & Insights

Expert strategies for designing a fintech marketing plan that drives growth and engagement.

All the Regulation in the World Won’t Stop the Next Crash

Balancing prudent banking practices with regulatory frameworks is crucial for economic stability and growth.

Top 4 Fintech Marketing Obstacles

Explore the top 4 challenges facing fintech marketers today and discover actionable strategies to overcome them.

Stars, Stripes, and Savings: 4th of July Spending Trends for American Consumers

Let's reflect on how American spending habits are shaping up for this year's 4th of July celebrations.

A Conversation on Financial Inclusion

Vested CEO Binna Kim and Abacus Federal Savings Bank CEO Jill Sung discuss financial inclusion during an event at Vested HQ.

The Sunday Times Best Places to Work

Vested UK was recently named one of the Best Places to Work by The Sunday Times.

Abby Trexler Joins Vested as Managing Director

Abby Trexler joins Vested as Managing Director where will lead the agency's South Florida practice.

Abby Trexler

How Reliable Is Jerome Powell at This Crucial Time?

With high inflation and an upcoming election, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell faces a difficult balancing act.

Vested Banking Breakfast with Chief Economist Milton Ezrati and US CEO Amber Roberts

Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati joined US CEO Amber Roberts to discuss the key challenges facing the banking sector.

Tips for Communicating with Employees During a Spin-Off, Demerger or Divestiture

Vested Managing Director Ted Birkhahn shares the importance of employee communications when it comes to spin-offs.

Becoming B Corp Certified as a Wealth & Asset Manager

Bailard, a top wealth and asset management firm and long time Vested client, has officially received their B Corp certification after completing the process earlier this year.

China’s Prospects Are Far from Bright: Most of Its Wounds Are Self Inflicted

China’s economic future is dimmer than its shining past. Most of its problems originated in the Forbidden City.

Comms Lessons from Paramount’s Leadership Upheaval

When there’s a shakeup at the top of an organization, the impact cascades through the organization, creating ripple effects well beyond the executive level.

Changing the World of Finance

In partnership with Financial Narrative, Vested UK hosted three industry trailblazers, talking about the change they were making institutionally and individually within the financial services sector.

Proactive Strategies for Communicating About Activist Investors

Recent proxy battles offer insights into how communications can get out in front of the drama.

Fitch Takes A Dim View Of China’s Financial Outlook

Fitch, the credit rating agency, has announced that it harbors doubts about the future of Chinese finance.

The Art of Persuasion: Media Interviews as a Performance

Learning how to deliver a great media interview that ultimately results in positive coverage requires practice, refinement, and technique.

April is National Financial Literacy Month

We're breaking down financial literacy and why it matters, plus sharing the stats that will change the way you think about it.

Vested Embarks on Marcomms Degrees Tie-Up With London University

Financial PR and marketing agency Vested is helping City, University of London to deliver marcomms degree courses and support new talent joining the industry.

Vested View: The Value of Pressing Pause

We sat down with Millie Graham, Account Director at Vested, to discuss her recent sabbatical and what she got up to during her time away.

Consumer Confidence Amid Uncertainty

With inflation in the UK at a standstill and global elections looming, consumer confidence takes a dip.

The Post-ChatGPT Playbook: Key Learnings about Communicating GenAI

Key learnings from Vested's experiences on consulting with and advising our clients on generative AI.

Vested Announces Leadership Expansion

Vested names new UK CEO and a Managing Director to oversee creative and marketing services.

A Day in the Life of a Vested UK Account Executive: Caitlin Ellis

A day at Vested in the life of Account Executive Caitlin Ellis.

Danger in the Puzzling Jobs Picture

With employment figures showing nearly 700,000 new jobs in December and January, Vested's Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores the factors that contribute to the full employment picture.

Sustainable Snapshot: Valentine's Day 2024

Tune into Sustainable Snapshot, the video series with Vested Director Marian Daniells and AssetTV.

Valentine’s Day Spending 2024: The (Spending) Power of Love

The National Retail Federation projects total spending will approach $25.8 billion on Valentine’s Day in 2024.

Ted Birkhahn Joins Vested as Managing Director

Ted Birkhahn joins Vested as Managing Director where he will lead the firm's strategic push into the middle market.

Ted Birkhahn

Bitcoin Again: This Time Bigger and Better

In light of the SEC's approval of Bitcoin ETFs, Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores Bitcoin's volatility and investment value.

Sustainable Snapshot: Green Asset Ratio

Tune into Sustainable Snapshot, the video series with Vested Director Marian Daniells and AssetTV.

Still 'a topic of hand-wringing': Four years after COVID began, agency RTO policies are yet a work in progress

Firms generally want employees in the office at least two days a week, but questions continue about whether to mandate attendance, how to monitor it and other factors.

The Great Rate-Cut Debate

When can we expect to see the much-anticipated Federal Reserve interest rate cuts? Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores all of the possible scenarios.

The Impact of Marketing Automation for Financial Services

Discover the impact of marketing automation for financial services brands, including key benefits and use cases for the finance sector.

Social Media Star Erika Kullberg Shares How to Avoid TikTok Scams and Get Rich the Right Way

Vested Managing Director Eric Hazard shares the importance of evaluating a TikTok commentator’s financial experience before taking any advice with InvestorPlace.

Vested 2023: It’s a Wrap

EMEA CEO Elspeth Rothwell reflects on a wonderful year of growth, collaboration, and partnership.

2023 Marks Another Landmark Year for Vested

As 2023 comes to a close, Vested has won numerous awards and recognitions that support the agency’s continued rapid growth and commitment to delivering unparalleled creativity to the financial services industry.

Whither the Private Debt Boom

Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores the history of private lenders and how they've come to control some $1.5 trillion of debt.

Thanksgiving Spending 2023: The Good, the Bad, and the Turkey

With another Turkey Day right around the corner, we here at Vested are thankful for a lot this year, like great clients, a growing team, and the Fed continuing to pause rate hikes. One of the things we’re most grateful for? Catching a break in the price of turkey.

Are Banks Failing to Address the Unique Needs of Women?

Survey data suggests that financial anxiety among women has worsened in recent years, even as banks say that they are focused on addressing the specific needs of women. Vested CEO Binna Kim shares the importance of technology and data with The Financial Brand.

Stemming the Flow of Red Ink

As the Federal Reserve’s counter-inflationary efforts have raised interest rates, deficits and debt concerns have risen on the national agenda. Chief Economist Milton Ezrati breaks down the proposals presently emerging from policy discussions on how to combat the increase.

Fintechs Are Pivotal To Helping Younger Consumers Feel Confident Switching Banks

What moves the needle when it comes to younger generations changing banks? Vested Ventures CEO Eric Hazard shares the three main areas of focus for fintechs to build comfort with their consumers in this article with The Fintech Times.

Sustainable Snapshot: New Board Diversity Trends

Tune into Sustainable Snapshot, the video series with Vested Director Marian Daniells and AssetTV.

Dr. Claudia Goldin: 2023 Nobel Memorial Prize Winner in Economic Sciences

Dr. Claudia Goldin, Harvard professor and trailblazer, won the 2023 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

Qwoted Rolls Out Collaborative Industry Network

Qwoted released a new feature allowing users to search by agency, subject matter, expertise, job title or name.

China’s Self-Inflicted Wounds

Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati breaks down China's severe economic troubles.

How Communicators Help Employees Use Their Wellness Benefits

Vested Chief People Officer Loreal Torres shares the ways she communicates benefits with new and existing employees.

Sustainable Snapshot: Conference Season & Carbon Offset Programs

Tune into Sustainable Snapshot, the video series with Vested Director Marian Daniells and AssetTV.

Whither ESG Investing

Chief Economist Milton Ezrati shares the history of ESG investing in the United States and where the data shows us we're headed.

Vested View: Why is a Sabbatical an Important Part of a Career Journey?

After four years with Vested, Account Director George Pitt took advantage of Vested's three month sabbatical program.

Gen Z Favors Word of Mouth Over Marketing

Group Vested CEO Binna Kim shares her thoughts on the Netflix factor and what the younger generation expects out of their banking experience in this piece with American Banker.

Introducing Sustainable Snapshot

Introducing the Sustainable Snapshot, the new video series with Vested Director Marian Daniells and AssetTV.

Crafting an Ever-Evolving Editorial Calendar

Vested Managing Director Eric Hazard shares his advice on staying true to your organization's editorial objectives and how to make the most out of your content with PR Daily.

Top Agency Leaders Talk Tech

Group CEO Binna Kim joined PRWeek and Notified for a roundtable on the conversations agencies are having with their clients on technology and artificial intelligence.

Office Space: More Trouble For The Foreseeable Future

The real-estate impact of COVID lockdowns is empty office space and a lack of desire to return to in-person work full time. Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores the fallout and the longterm effects in this article originally published by Forbes.

China Is Dumping Its U.S. Treasury Bonds

China has begun to sell its vast holdings of U.S. Treasury bonds. Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores what this means for financial markets, Washington's finances, and the economy at large.

Is the UK a Hostile Environment for Bigwigs Who Forget the Basics?

Are there lessons to be learned from the recent NatWest fallout? Vested Associate Director Henry Adams examines the current environment in which the story is unfolding and and the implications for business leaders moving forward.

MAD//Fest 2023

Account Executive Marcus McGrigor shares his key learnings from this year's MAD//Fest marketing festival in London.

What Google Analytics 4 Means for Your Business

Google Analytics 4 (GA4) is here to stay and Universal Analytics has officially been retired. What does that mean for your organization and why does it matter?

Threads Is Huge. Sew What?

Meta’s Threads has been out only a few weeks, but it already has become a major player in the social space. But is it the Twitter killer everyone was anticipating?

The Future of Crypto

Recent SEC action against two of the world’s largest crypto exchanges have called into question the future of crypto. Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores.

Breakfast & Brainfood: B2B Marketing in the New Digital Era

The Vested UK team hosted a Breakfast & Brainfood event with LinkedIn and BlackRock with discussion about how marketers are engaging with institutional investment audiences in the new post-pandemic digital era.

Breakfast & Brainfood with Signal AI: Mastering the Art of Meaningful Metrics

The Vested UK team hosted an event in partnership with Signal AI focused on the innovative ways companies are looking at PR and marketing measurement.

Another Housing Crisis?

Chief Economist Milton Ezrati talks about the ongoing housing crisis, and what we can learn from the collapse of 08-09.

Is the Fed Done?: Interest Rate Predictions

Chief Economist Milton Ezrati looks at recent actions by the Fed to predict what's next for interest rates. Spoiler alert: there are likely more hikes to come.

Navigating Communications Trends and Challenges

Group Vested CEO Binna Kim joined PR’s Top Pros Talk to discuss leadership styles, the challenges communicators face in today's environment, and how we can leverage both data and a variety of channels to mitigate the issues our clients face.

The Bamboo Ceiling: Being an AAPI Leader

Less than seven percent of PR and advertising professionals identify as AAPI. Very few AAPIs are represented in the C-suite amongst the top PR agencies. Beyond the communications industry, AAPIs run into the “bamboo ceiling,” and AAPI women, in particular, find themselves crashing into the “bamboo glass ceiling.” Group CEO Binna Kim writes for O'Dwyer's.

How Does the Inflationary Environment Impact How We Communicate?

The UK may be on track to dodge a recession this year, but inflation concerns remain high. Account Director Amelia Graham explores what this means for both consumers and businesses and how brands can communicate clearly to support their customers during these volatile times.

Is the digital dollar likely?

Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores the implications, roadblocks, and advantages of the digital dollar after a resurgence of interest, in this article originally published by Forbes.

Whoa, Mama: 2023 Mother's Day Spending Up $4 Billion

Despite a looming recession, data from NRF indicate that 2023 Mother’s Day spending could increase to as much as $35.7 billion - the highest year on record.

Is America Recapturing Manufacturing?

After decades of decline, American manufacturing is making something of a comeback. Chief Economist Milton Ezrati dives into the investment spending in new facilities and how a surge could impact employment.

On Embracing AI

With artificial intelligence dominating in the business news cycle, there's a lot of talk about innovation and the future. There's also a lot of talk about the drawbacks or dangers of the emerging technology. In this article originally published by Forbes, Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati helps readers move past their fears and focus on embracing AI.

How Can Businesses Celebrate Earth Day Authentically?

How are your Earth Day comms shaping up? Account Director Megan Lloyd shares her top pointers for brands planning to weigh in.

The Budget Deficit Continues

The budget deficit continues to widen, but what exactly does that mean for the US? And what exactly could be done about it? Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati breaks down the issues in this article originally published by The Epoch Times.

Firms Dial Up Advertising to Draw Market-Shy Investors

Continued market turbulence may mean wealth management firms are allocating more advertising resources to investors looking for advice. Vested CEO Binna Kim weighs in on why firms need to simplify their messages to break through to consumers.

After SVB Collapse, Regional Banks Hustle to Protect Their Reputation

Vested US CEO Amber Roberts weighs in on how her teams are responding to the aftermath of the SVB collapse and the importance of communications in uncertain times.

You Can Bank on This Crisis Communications Toolkit

In the finance world, bad news travels fast, and rumors travel even faster. All PR professionals know that in a crisis situation, every second you’re not actively participating in the conversation is a strike against you. The Vested Crisis Communications toolkit provides you with guidance that all FinComm pros can follow when planning for and responding publicly to organizational emergencies.

Maximizing the Vested Media Map

The recently launched Vested Media Map is a great tool to uncover valuable media trends and insights to help you stay ahead of the competition. This deep-dive video will help you discover how to maximize its potential.

What Is the Outlook for Challenger Banks Following the Collapse of SVB?

In the wake of the SVB collapse, challenger banks have the opportunity to pick up customers who have lost their faith in traditional banking brands by positioning themselves as the alternative.

Inflation Woes Continue

The inflation issue has been tough to crack, with numbers creeping back up after a brief period of hope that we may be through the worst. Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores in this article originally published by Forbes.

College or Career?: The Jobs-College Split

For decades now, a college degree has been considered the only means to a good job, a “ticket to the middle class,” as many in media and in politics say. But in today's environment, that may no longer be the case. Vested's Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores the jobs-college split.

How Will Recent Bank Failures Impact the Economy?

Chief Economist Milton Ezrati joins KNX Radio to discuss whether the American banking system is really safe and if the economy will be impacted.

Silicon Valley Bank, Rising Interest Rates and Banks

Silicon Valley Bank has failed. Chief Economist Milton Ezrati analyzes how we get here, the Fed's action, and what it means for banks moving forward.

International Women’s Day: Embrace Equity

This International Women’s Day, we’re celebrating the theme “Embrace Equity,” which focuses on promoting gender balance and inclusion in all areas of society.

Commercial Real Estate Outlook, February 2023

The post-COVID recovery has been a mixed bag for most industries. Chief Economist Milton Ezrati looks at the numbers to help understand the commercial real estate outlook for 2023.

PR and Communications Resources for Growth

During times of turmoil, smart orgs get resourceful. There are many free or low-cost resources that can help early-stage brands carve out a competitive advantage in the PR and marketing communications space. These are some of Team Vested’s favorites.

Vested in the News: Milton Ezrati on the 1980s Recession

Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati was quoted in "Why the 1980s recession haunts the Fed," published online by The Hill on February 6th, 2023.

Technology and the Future - Part 2

In part 2 of this series originally published by The Epoch Times, Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores the economic impact that technology will have on the future, with an eye toward ESG and the aging retiree population.

Charting the Media Landscape with the Vested Media Map

Vested is excited to announce the official launch of the Vested Media Map, a real-time dashboard of top media topics across core industries.

5 Financial Leaders We Celebrate for Black History Month

These financial professionals may not be household names, but we think you’ll agree their accomplishments deserve recognition. Here are five Black Americans we’re honoring at Vested this Black History Month.

ChatGPT Wrote My Article For Me

Vested Chairman Dan Simon uses ChatGPT to write a whole article for him promoting Qwoted, Vested's tech platform.

Technology and the Future - Part 1

Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores the future impact that technology will have on the economy through the lens of data, communication, fintech, and healthcare, in part 1 of this 2-part series, originally published by The Epoch Times.

Inflation impacts consumer spending

With inflation far outpacing recent wage gains, consumer spending in key categories is down. Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores the far-reaching impacts in this article originally published by Forbes.

Are Bonds Back? Well, Yes, Sort Of.

The Fed's efforts to ease inflation have given investors reason to include bonds in their portfolios for the first time in a decade. Chief Economist Milton Ezrati examines what the renewed interest in bonds means for investors as the world’s central banks raise interest rates higher still.

The Role of Reputation in Uncertain Markets

With market fluctuation and economic uncertainty at a high, brands are under increased pressure to manage their reputations. Director Jo Field examines how increased scrutiny impacts communications strategies.

Housing Depression Will Continue

After a volatile 2022, the housing market continues to make waves in the new year. Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores in this article originally published by The Epoch Times.

Does hiring signal strength?

In early January 2023, hiring remained strong. But does hiring signal strength for the rest of the economy? Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores in this article originally published by The Epoch Times.

Chairman Dan Simon Named to PRWeek Dashboard 25

Each year, the Dashboard 25 recognizes top leaders in the communications technology space and celebrates the innovators driving the PR industry forward.

Consumer cutbacks in 2023

Between inflation and rising interest rates, consumers have been cutting back on spending, increasing the looming threat of recession. Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati weighs in in this article originally published by The Epoch Times.

The Vested Partner Program

After four years of service, Vested employees are eligible to join the partner program, which offers executive coaching, professional development and other perks.

Jobs Strength Won't Last

Jobs strength has continued to grow in face of an increasingly volatile economy. Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati puts it all into context in this article originally published by Forbes.

At the Vested Bar with Shari Dodgen: Vice President of Global Corporate Marketing at Trintech

Shari Dodgen, Vice President of Global Corporate Marketing at Trintech, sits down at the Vested bar to discuss communicating with a global mindset, speaking to various, complex audiences, and how the culture at Trintech has evolved thanks to powerful female leadership.

Progress Against Inflation

In recent weeks, the Fed has made significant progress against inflation. Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati reviews impacts so far and what we can expect next in this article originally published by The Epoch Times.

Song of Sam

Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati weighs in on the FTX collapse, Sam Bankman-Fried, and how we got here in the first place.

A Look Back at 2022, a Look Forward to 2023

‘Tis the season for articles that look back at the past year and forward to the next. Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati looks back at the wild ride that was 2022 to give us a clearer view of 2023 in this article originally published by The Epoch Times.

The Best of Vested: 2022 in Review, Q4

The final article of our 4-part series explores the top Qwoted content of Q4 2022.

The Best of Vested: 2022 in Review, Q3

This is part 3 of our 4-part series on 2022 in Review. As we prepare for 2023, we look back on a year of Vested content. This article looks at our top content from Q3 2022.

The Best of Vested: 2022 in Review, Q2

This is part 2 of our 4-part series on 2022 in Review. The end of the year is a time for reflection. As we prepare our resolutions for 2023, we look back on a year of Vested content. This article looks at our top content from Q2 2022.

The Flap Over ESG

ESG investing has been in the headlines frequently as of late. In this article, Chief Economist Milton Ezrati breaks through the noise to define the major players and their interests regarding ESG regulation.

Inflation Impacts Holiday Spending, Gaudy Yard Decorations

If you noticed that Black Friday somehow became Black November this year, you’re not alone. With inflation ravaging budgets, retailers decided to meet consumers where they were at, with one of the earliest, longest holiday shopping seasons on record. Explore how inflation impacts holiday spending with Vested.

A New Standard in Climate and Investing: Most Effective Content Marketing Campaign 2022, Financial Services Forum Awards

The Vested UK team led the go-to-market strategy for CFA UK’s Certificate in Climate & Investing, which resulted in winning the Most Effective Content Marketing Campaign 2022 at the Financial Services Forum Awards.

Financial Services Brands on Twitter: Should They Stay or Should They Go?

What does Elon Musk's Twitter takeover mean for brands and advertisers who rely on the platform? Vested's social media experts share the advice they’ve given to financial services clients about posting and advertising on Twitter during this uncertain time.

Credit-risk Transfers: A Financial Vulnerability

Looking back to the 2008-2009 financial crisis for guidance, Chief Economist Milton Ezrati explores what may be one of today's greatest vulnerabilities in the face of a potential recession: credit-risk transfers.

Gobbling Up a Little Less: Inflation and Thanksgiving 2022

With Thanksgiving right around the corner, US Americans are preparing for stuffing—the side dish and themselves. But with inflation ravaging the economy and threat of recession on the horizon, many are tightening the elastic on their stretchy pants.

UK SMEs: Optimism in the face of challenge

The Vested UK office recently hosted a Breakfast and Brainfood event and welcomed back Shiona Davies, author of the BVA BDRC SME Finance Monitor to update us all on today’s SME landscape.

The US Economy is Sick

As we stand on the precipice of a recession, one thing is clear - the economy is under the weather. Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati looks at earnings, inflation, and GDP to offer insights about our current situation.

Is Small Talk at Work Necessary to Succeed?

Vested Group CEO Binna Kim weighs in on how small talk can help build relationships at work and how employers can think about it in this article originally published on WorkLife.

What Is a Communications Professional’s Role in the Face of War and Crisis?

In times of crisis, communications professionals have to determine the right actions, provide expert counsel, and execute with compassion and tact. Account Executive Gabby DiCarlo examines the steps professionals took during the start of the Ukraine crisis and offers a path for moving forward.

At the Vested Bar with Jessica Zaloom: Head of Corporate Communications at WisdomTree

Jessica Zaloom, Head of Corporate Communications and Public Relations at WisdomTree, sits down at the Vested bar to discuss marketing to various audiences, her advice for those breaking into the industry, and how she successfully partners with her Vested team.

Understanding, Trust, Tone and Thoughtfulness: The Armory of Communicators

Managing Director Katie Spreadbury joined Signal AI to discuss the opportunities and challenges that a recessionary environment presents to B2B communicators. Dive into what she learned and how the panelists believe communicators can be most valuable to their consumers during times of volatility.

The CHIPS for America Act: A Strange Mix

Chief Economist Milton Ezrati takes a deep look at the CHIPS for America Act - a new bill devised to spur semiconductor manufacturing in the US.

The UK’s not so ‘mini-budget’ could have a major impact

Since mid-summer, debates surrounding what the new conservative leader and Prime Minister would do to tackle the cost of living crisis have been widespread. Now that we know it is Liz Truss, the country’s attention is very much fixed on her to deliver a plan.

How Founders Get More Sales in Their Startups

Vested Ventures CEO Eric Hazard joins Making Billions with Ryan Miller to discuss the right messaging when raising capital and the benefits of the PESO model.

Vested Steps Behind the Camera

Account Assistant Marcus McGrigor got a taste of the media training and preparation he puts clients through with a series of mock interviews designed to make it feel like you're presenting to a live audience.

For the Love of Campaigns!

Campaign work can be rewarding, intriguing and challenging. Managing Director Katie Spreadbury explores the campaign process, the magic of collaborating with a team, and the moment when a complex idea comes to life.

Financial Communications Leader: Scott Stanzel

Scott Stanzel named Chief Communications Officer at Truist.

Investing in Fintech with an Impact

Vested Ventures CEO Eric Hazard joins The Compassionate Capitalist podcast to discuss the nuances within fintech and how its uniquely qualified to address issues with financial access.

5 Considerations When Developing Your ESG Strategy

Learn how ESG-focused industry leaders build strategies in their own companies and the 5 key points to consider when developing your own ESG policies.

Financial Communications Leader: Jennifer Lowney

Jennifer Lowney named Global Head of Communications at Citi.

Cost of Living Crisis: How Does It Impact How We Communicate?

As the cost of living crisis continues to take its toll and inflation is expected to peak above 10% later this year, Account Director Amelia Graham explores what it means for both borrowers and savers in real terms and ultimately how brands communicate with their customers.

A Break in Inflation?

July brought a measure of relief on the inflation front, but one month does not make a trend. Chief Economist Milton Ezrati digs into details from the latest CPI report and offers insights about the ongoing economic situation in this article originally published in Forbes.

Financial Communications Leader: Brenda Tsai

Brenda Tsai named Chief Communications Officer at State Street.

Financial Communications Leader: Pablo Rodriguez

Pablo Rodriguez promoted to Head of Communications for the CCB group at JP Morgan Chase.

Landing a PR Job After Graduation

Between the applications, interviews, and waiting games, the process of landing a PR job after graduation can feel very overwhelming. After spending years learning a new skill set you suddenly are facing a brand new challenge - breaking into the job market. Senior Account Executive Madison Perrott shares tips to stand out from the crowd and better position yourself to land a job after college.

Will The Fed's Latest Move Be Enough to Combat Inflation?

Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati joins Yahoo! Finance Live to discuss whether the latest move by the Fed will be enough to combat inflation.

The Difference Between Paid, Owned, & Earned Media

There are many ways of getting your organization’s message across to the world. Broadly, these fall into three categories: Paid Media, Owned Media, and Earned Media. Each of these PR channels have their own strengths and weaknesses, and each serves an important role in developing a strong media mix.

Plain Speaking Needed To Make Sense of E, S and G

Vested Associate Director Henry Adams examines the complexities of ESG and how leaders and businesses can be more specific about their agendas.

How To Crush Your Next Interview

Vested Senior Account Executive Madison Perrott interviewed Talent + Culture Specialist Nikki Barachina to discover tips and best practices to nail the interview process.

At the Vested Bar with Ian Miller: CMO at Agile and MCT

Join Keren Unrad, Vested's Head of Marketing as she interviews Ian Miller, Chief Marketing Officer at Agile and MCT. They explore the development of Agile’s brand and messaging from the ground up and how Vested’s 360 process and experience in the fintech space were deciding factors in working with the agency.

Financial Communications Leader: Rob Cox

Rob Cox named Global Head of Corporate Communications at Credit Suisse.

Financial Communications Leader: Amy Bonitatibus

Amy Bonitatibus named Chief Communications and Brand Officer at Wells Fargo.

Group Vested Executive Leadership Expands Responsibilities Amid Double Digit Growth

Group Vested made several changes to its executive leadership team's titles at the beginning of this month to more accurately reflect the team's responsibilities.

What It Means to Win Awards

Elspeth Rothwell, CEO of Vested EMEA, reflects on what it means to win the CIPR Specialist Consultancy of the Year award.

Give Me Liberty or Give Me Debt: Exploding Cost of Fireworks

With the 4th of July approaching, many are getting ready for travel, cookouts, and the All-American Fireworks Spectacular. But with supply chain issues and inflation ravaging the economy, the cost of Independence Day celebrations is higher than ever, and many fireworks displays across the country are being canceled as a result.

Humanising Brands Is the Key to Unlocking Meaningful Relationships

Vested hosted a breakfast event in collaboration with LinkedIn to discuss the trends from the Finfluence Report that will drive the agenda for FinServ marketers over the next year and beyond. Learn more about what was discussed and where we can go from here.

Father's Day Spending Index 2022

For many, Dad taught us our earliest financial lessons. Turn off the lights. Don’t touch the thermostat. You don’t need new shoes until your white New Balance sneakers are completely green from mowing the lawn 1,000 times. You know, the basics. With Father’s Day a few days away, most of us will be looking for a way to repay the man who raised us for all the insights, encouragement, and lessons in frugality.

The Many Mysteries of Decision Making

Joseph Devlin, Vice-Dean at UCL and a leading specialist in the sphere of neuroscience and marketing, shares how our brains impact decision making, even when it comes to brands and services.

At the Vested Bar with Lynn Kier: VP of Corporate Communications at Diebold Nixdorf

Join Keren Unrad, Vested's Head of Marketing as she interviews Lynn Kier, Vice President of Corporate Communications at Diebold Nixdorf. They dive into the power of storytelling in marketing, how to use global teams and perspectives to the benefit of consumers, and how Lynn boosts women in a male dominated industry.

How To Bring More Care into Your PR Workplace

When employers show they care for their employees, it creates a cycle that positively impacts not only the business, but clients too. Vested managing director Katie Spreadbury shares her thoughts on creating a caring culture with PRmoment.

LinkedIn-spiration: 4 FinServ Companies to Emulate on LinkedIn

Need inspiration for your corporate LinkedIn page? Check out these four best-in-class examples to revamp your existing strategy.

Vested Campus Day 2022

In May 2022, Vested celebrated Campus Day at our New York HQ. We gathered more than 50 Vesties from around the world for a day of connection, learning and fun. Hear from some of our colleagues about what made the event so special and why they love the space.

Decentralized Leadership is Key to Organizational Change

Decentralized leadership is the key to progressive organizational change. It's also a reflection of our increasingly decentralized world.

Queen Elizabeth II, The Platinum Jubilee, and How Things Have Changed

In celebration of the Queen's Jubilee and a long weekend in the UK, account assistant Zuhur Ahmed looks at just how much has changed over the last 70 years when it comes to money.

Reshaping the Leadership Paradigm Will Help AAPI, Others

As Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month comes to an end, Vested president Binna Kim weighs in on how we define and promote leadership within corporate America.

Inflation Will Lead Inexorably to Recession

With inflationary pressure confronting the economy, Chief Economist Milton Ezrati believes recession is on the horizon. Here, he shares his thoughts on timing and outcomes with Forbes.

Eric Hazard Talks Financial Literacy and How to Manage Its Complexities

Vested managing director and CEO of Vested Ventures Eric Hazard joins NBC News Radio to discuss financial literacy and how people can get started on the path toward a more informed financial future.

How Inflation will Impact the Cost of Your Memorial Day Picnic

Inflation is driving up the price of just about everything these days. That means your Memorial Day picnic is going to be a bit pricier this year.

Milton Ezrati on the Economy, Housing Market and the Possibility of an Upcoming Recession

Vested Chief Economist Milton Ezrati joins managing director Jacqueline Gogel to discuss the current housing market and whether the economy is positioned for recession.

The Evolving Attitudes Toward Mental Health: Q&A with Leadership Impact Coach, Simon Scott

As part of Mental Health Awareness Week in the UK, hear from leadership coach Simon Scott on the evolving attitudes toward mental health and his work with leaders across businesses.

PR Players Aim To Claim Their Space In the Metaverse

As brands fast-track their moves into the metaverse, industry watchers are urging communicators to proceed with caution. Vested's Binna Kim weighs in.

Scribe's Advisor Letter™: Best-in-Class Financial Content

Scribe’s Advisor Letters™ are pre-written market summaries and forecasts for financial advisors, RIAs, and thought leaders to share with readers. Choose from 3 levels of ready-to-send financial content marketing.

Financial Industry Free Fall Engages the Communicators’ Cavalry

No matter their politics, everyone seems to have headaches and anxiety about the current state of their finances. Stuck in the middle of all this are financial platforms, banks, and advisors. Communicators, once again, will answer the call and serve as the cavalry in a sea of confused and worried clients. Vested's Eric Hazard weighs in.

What Elon Musk Could Mean for Brands on Twitter

Elon Musk's takeover of Twitter could mean big changes (and problems) for brands.

May the 4th Be with You: The Economics of Nostalgia

On the holiest of holidays in Geekdom, we look at the value of original Star Wars memorabilia on today's market and see how the toys stack up against the S&P 500 over the years.

Investing in the Metaverse

Investing in the metaverse may not be as revolutionary as some believe.

TikTok #ForYou…and #ForYourBrand

Once thought of as an app for videos of dancing teenagers, TikTok has now become a platform for financial services brands and fintechs to create awareness among new audiences.

Aon Names Vested as North America PR Partner

Aon's Head of Global Communications, Mike Marinello, announces that Vested has been named as its North American agency partner.

Where IR and Content Meet

First quarter earnings are around the corner, a time when the Investor Relations’ pages of a corporate website start gaining real traction. The IR role is an important one and a good content strategy, like a solid quarterly earnings, can drive eyeballs to your site.

Vested Ventures Makes Strategic Investment in Fintech Startup, Qoins

Qoins is a financial planning app that helps users pay down debt and achieve financial goals through automation.

Buy Me Some Peanuts and Cracker Jacks, I am Never Going to Financially Recover from This

As baseball fans return to the stands, concession costs creep higher.

A Universal Basic Income?

Milton Ezrati gives his thoughts on the idea of a Universal Basic Income and thinks "the idea to give a free cash stipend to everyone is wrongheaded".

Modern Comms is More Substance than Style - a Reminder from EVRi

Earlier this month, EVRi (formerly Hermes), one of the UK’s best known delivery companies announced a complete corporate rebrand in a likely bid to remove itself from its toxic brand identity.

Five Facts About Women and Finance: Supporting Financial Literacy for Women

During Women’s History Month, we want to emphasize the importance of women increasing their wealth through education. Here are five facts about women and finance that should encourage you to prioritize financial literacy.

An Interview with Graduates of the Vested Graduate Associates Program

Recent Graduates of Vested's Graduate Associate Program Give New Applicants the Inside Scoop of What It's Like to Work at Vested.

From the Frontlines of Ukraine: Journalist Trades His Laptop For a Rifle

Until last week, Yuriy Matsarsky was a Ukraine-based journalist. Today he's a soldier defending his homeland. Listen to the powerful interview conducted on Friday, March 4 by Qwoted's Editor In Chief, Lou Carlozo.

Vested Ventures Provides Strategic Investment to Financial Planning Software Company Anasova

Vested Ventures funding will help the company develop their financial Anasova advance and promote their mission of minimizing the stress around finances through free financial planning tools.

What's the Deal with the Digital Dollar?

With cryptocurrencies gaining in popularity, is the digital dollar far behind?

Building Financial Resilience With America Saves Week

America Saves Week is happening now! And this year’s theme is all about building financial resilience. Here are America Save’s top five tips for boosting your financial resilience this week.

A Day in the Life of a Vested UK Account Assistant: Marcus McGrigor

Life at Vested is pretty fast-paced, but that is why I love it!

Valentine's Day Spending: How Much Do People Spend In The Name Of Love?

Valentine’s Day spending is expected to hit $23.9 billion in 2022, with the average person doling out around $175.41 on their significant other. Here’s a closer look.

In defence of EastEnders - how pop culture shapes finance

Self-professed financial services geeks shouldn’t care about who killed whom on EastEnders, right? Corporate business strategies bear no relation to Keeping Up With The Kardashians… Well… not quite. Celebrity and pop culture has always influenced the status quo, which in turn impacts how consumers interact with financial services firms. As well as the social reforms that came about thanks to his writing, Charles Dickens is widely accredited to have given us the cultural blueprint for the ‘traditional’ Christmas we know today.

The Other D: Accessibility and Access for Employees with Disabilities

Vested's Managing Director, Bryan Limon, describes what it's like to live and work with disabilities and steps employers can take to make workplaces more accessible.

Robinhood's 2021 PR Crisis

Vested's Eric Hazard comments on Robinhood's 2021 PR crisis in PRovoke Media's roundup of the top 20 PR Crises of 2021.

2022 Predictions from PR Experts

Top PR Execs, including Vested's Binna Kim, Give Their Predictions for 2022.

It's A Wrap: 2021 Edition

It’s beginning to look a lot like… the end of an amazing / challenging / exhausting / exhilarating / incredible year! Take your pick, all and any of those words sum up the last 12 months for me and so much more.

2021: The year we all moved the dial on the treadmill a little...or a lot

2021 has been a year of recalibration, but also one of optimism. After the seismic global shift which emerged out of nowhere in 2020, we picked ourselves up, dusted ourselves off and moved forward with purpose.

Planning for 2022 with resilience, creativity, flexibility, purpose and empathy

As we near the end of another year of change for the communications industry, we hosted a webinar with Signal AI, looking at the opportunities for communicators in 2022.

What Does the IPO Surge Say?

What the IPO flood reveals is that a large and diverse group of presumably savvy business people see a bright economic future and a market that might be pricing itself for something even brighter than the reality they see. It is a view that investors need to consider and one to which the flood of IPOs has called attention.

Do "Buy Now, Pay Later" Services Like Klarna Trick You Into Debt?

Are you thinking about using a “buy now, pay later” service like Klarna or Afterpay this holiday season? If so, here’s what you need to watch out for.

4 Common Types of Financial Fraud & How to Avoid Them

In honor of International Fraud Awareness Week, we’re uncovering four common types of financial fraud and how to avoid them. Click the link to learn more.

A day in the life of a Vested Account Assistant: Budget Day edition

Buyer Beware: The Rise of Digital Investing and Why Education is Critical

The Rise of Contactless: A Penny for your Thoughts?

10 Fresh Marketing Ideas For Financial Services